- Home

- Karina Halle

Darkhouse (Experiment in Terror #1) Page 2

Darkhouse (Experiment in Terror #1) Read online

Page 2

After I told her I’d be there and hung up, I stretched back on my bench, the sun heating up my maroon leggings, and half-heartedly nibbled on some cut-up veggies. I eyed a nearby Subway and almost succumbed to the call of a melted bacon sub but resisted.

I finished up and plodded back to the office, defeated by the drudgery of the nine-to-five life. The sun teased the freckles across my nose and the lightest breeze tossed my hair so I could see the shades of violet dye in the black strands. I wanted to stay outside, surrounded by the quaint buildings, the golden green trees, the people bustling to-and-fro in lives more exciting than mine, and most of all I wanted these last rays of summer to last forever. But duty called, as it always did.

I walked into the lobby and waited for the elevator. As I stood there on the cold, hard tiles, I felt the presence of someone behind me. Strange, I didn’t see anyone when I came in, nor did I hear the door open or close behind me.

A creepy feeling swept over me. I remembered the dream I had. Suddenly, I felt inexplicably afraid.

I hesitated at turning around. In my “overactive imagination” I thought I would see something horrible, but I did it anyway.

There actually was someone there sitting on the white lobby couch. It was an old lady who looked like she was trying disastrously hard to be a young lady. She must have been about eighty, wearing a red taffeta dress adorned with tiny pom poms and outlandish makeup smeared across her face. She had exaggerated purple eyeliner, Tammy Faye Bakker eyelashes, a swipe of orange across her sagging cheekbones, and most disturbing of all, red lipstick that was half on her lips and half on her teeth. She sat there smiling broadly at me. Frozen, it seemed, or locked in time.

I tried to hide my shock—I don’t know how I didn’t see this piece of work when I came in—and gave her a quick smile before promptly turning around. I felt relieved when the elevator doors finally opened.

I walked quickly inside and hit the close button before anything else. I looked up at her as the doors closed. She was as still as ever, the wide, maniacal-looking grin still stretched across her face. Her eyes, white and unblinking, did not match her smile.

The doors shut and I let out a large sigh of relief. I had actually been shaking a little bit. That horrible feeling lasted for another five minutes until I slipped on my headset and the daily barrage of rude callers and impatient visitors wiped the scene out of my head.

CHAPTER TWO

“Is that what you’re wearing?” my mother asked.

It was ten a.m. on Saturday, and I was too tired to handle anything coming out of my mother’s mouth.

Ada and I were loading our luggage into my parents’ car when my mother spied the outfit I had on for the day. From her tone, I assumed it wasn’t “family appropriate,” though it was pretty much what I wore every day. Combat boots, black leggings and a long mohair sweater with deliberate rips throughout it.

I sighed and tossed my bag in the car. I put my hands on my hips and glared at her. She stepped into the passenger seat slowly, neatly, wearing a black shift dress with yellow strappy wedges and matching trench coat. Her perfectly highlighted blonde hair was piled into a loose bun on top of her head and framed with huge Chloe sunglasses. She looked like the perfect Hitchcock heroine and I wondered if that’s why I had such an affinity for Hitchcock’s films. But then I noticed the disappointment in her face, realized how inappropriately she was dressed (we were going to the beach, for crying out loud) and remembered I liked Hitchcock’s films because of their macabre view of mankind.

“Why, what’s wrong with it?” I asked her while exchanging a glance with Ada. She shrugged with a don’t get me involved look in her eyes.

“You’ve got holes in your sweater, dear,” Mom said. “Your cousins will think we can’t afford to get you new clothes.”

“Oh, whatever Mom,” said Ada, who was dressed sensibly in pastel skinny jeans, ballet flats and a black furry vest over a shrunken Alice in Chains T-shirt (which was my shirt, of course. Like she knew who AIC was). “The original price of Perry’s sweater was well over $100; luckily she got it for $40.”

I frowned at her while we got in the back of the car. I had no idea how she knew such random things about my life.

Knowing what I was thinking, she added, “I saw it for sale online. I knew you’d buy it. It’s just skuzzy enough.”

“OK! Off we go!” Our father’s bellow shook the whole car as he jumped in the front seat. He adjusted the rearview mirror and gave us a wink. Thankfully, he didn’t hear our conversation because anytime money was mentioned in our family it just became primer for a blazing argument.

Dad was a robust man with a hearty laugh and a heartier appetite (hence his ever-expanding “wine” belly), who identified dearly with his Italian heritage. Though he and his brothers were second generation Italians, you would never know it. They spoke Italian fluently, especially with their hands. It was dangerous to get my father talking when he drove, or anytime really. I remembered when Ada and I bought him this Italian classic film collection and in his enthusiasm he whacked me in the face. I think my mom was quite pissed off after that, probably because my dad does have quite the temper as well. Don’t get me wrong, my father has never purposely hit me or anyone in my family, but when his face turns red, his cheeks puff out, and his small stature suddenly becomes about ten feet tall, he becomes the most feared creature on earth.

He’s a bit of a workaholic too, which doesn’t help. He’s a history and theology professor at the University of Portland, so we don’t get to spend as much time with him as we probably should.

I get more traits from my father than I do from my mother. We’re both overtly sensitive but with me, I can’t hide it. Sometimes I feel like I’m just a giant orb of vibrations and feelings that knocks everyone flat on their back, whereas my dad just puts it somewhere else (fuel for a later explosion). One big difference between us is his unwavering faithfulness. He just accepts things and moves on. I always have to question, always have to argue and always have to ask why until I’m blue in the face. I wish I could let things go as easily as he does.

For example, on this day, as my father drove us down the I-5 at a leisurely pace, I couldn’t stop thinking about yet another dream I had, whereas he would just pass it off as an ordinary nightmare and move on. But as long as I’ve been alive, “ordinary” was a term rarely applied to me.

Last night had been a normal Friday. I practiced a few songs on my guitar (I felt guilty for having neglected it), did laundry and watched a Family Guy episode or two before hitting the sack. Maybe it was the coffee I had so close to bed, but I couldn’t sleep for the longest time. I just tossed and turned as my ears picked up the slightest sounds, from Ada snoring lightly down the hallway to the faint rustle of the maple tree outside my window. Even the glowing numbers from my alarm clock made my room turn into a supernova.

I must have fallen asleep at some point in the night because I woke up with a start. My body felt ice cold from the inside out, like an IV drip was seeping into my bones and filling them with liquid terror. My breath was frozen. All my limbs were outside of the sheets, stiff as boards. They felt exposed and naked and I had visions of some monster coming and gnawing at them, or perhaps a small hand coming out from underneath my bed and peeling my toes and fingers off. I wanted nothing more than to stick my arms and legs inside my sheets and keep them safe. The fear was so real.

But I couldn’t move. Not because it was physically impossible but because I didn’t want to.

Someone was standing in front of my door. At first, I thought it was my housecoat hanging on the hook. My room was as dark as I’d ever seen it, and without turning my head to look, I knew the lights on my clock went out. As my eyes adjusted to the depths, I remembered that my housecoat was still in the dryer and this “thing” had dimensions and breadth to it.

I lay there watching it for what seemed like minutes. I don’t think I breathed once for fear of drawing attention to myself. I didn’t know

what it was, but it kept very still, which was more disturbing. Sickening shivers worked up my spine.

A spotlight suddenly flashed through my room in one swoop, illuminating everything with precise intensity. For a split second I saw the thing. Saw a hooded coat made of oily, wet fur and then a face, no eyes, but one wide, white smile. The smile parted. Black gums. An abyss.

And then…

BLAAARP!

My alarm went off.

And in an instant it was the morning. Bright sunshine filled the room, exposing its harmless nooks and crannies. There was nothing at the door and everything was as I had left it. Gentle wafts of bacon and coffee drifted in from downstairs. It was just another dream.

I shuddered at the memory. My mom eyed me suspiciously in the rearview mirror.

“That’s what you get for wearing a sweater with holes in it.”

The air conditioner that my father had on full-blast definitely didn’t help, but I rolled my eyes and leaned my head on the cool window. Cars zipped past in all directions, the fields by the highway were bright green under the sharp, clear sky and defying autumn’s cold approach. Next week would be October and it still felt as fresh as a June day. At least we had that. My dreams would be a lot more poignant had we been enraptured in the normal fall weather of dark skies, howling winds and driving rain. Normally I loved the storms and the prickly atmosphere that went with Halloween and all things creepy. But two scary and remarkably realistic dreams, plus one alarming stranger in the lobby, and this accompanying anxious feeling, all had me a bit on edge.

Feeling eyes boring a hole into the side of my head, I turned and saw Ada staring at me. In her hands was a fashion magazine, in her ears, her iPod. I noticed how perfectly manicured her nails were, the brilliance of the red polish and the preciseness of the application. I didn’t need to look at my own hands to know what they looked like.

She narrowed her azure eyes. “What is with you lately?”

“What?” I asked, a little too defensively.

“I haven’t seen you this spacey since…,” she trailed off.

I gave her a sharp look and didn’t dare look at my mom in the rearview mirror. I knew she was watching me carefully.

“I’m fine,” I said sternly.

She leaned in a bit closer and lowered her voice.

“Did you have another dream again?”

I sighed and nodded.

“Same one?”

“No, different. Still as f—,” I stopped, remembering where I was, “—messed up, though.”

“I didn’t hear you screaming your head off this time.”

That was enough for my mother to get involved. I knew she had been waiting for an opening.

“What are you talking about?” She turned in her seat to look at us and focused in on me with motherly concern. “Are you having nightmares, Perry?”

“I don’t know if I would call them nightmares,” I replied as nonchalantly as possible. The last thing I needed was for my mother to start worrying that I was going Looney Tunes. She’d always been far too eager to jump to that conclusion.

Ada snorted. “She woke me up yesterday with her screams, totally messed up my morning routine. You should be glad you were out jogging mom; she was a mess. Totes.”

I shot Ada a look, more annoyed at her use of the word “totes” than anything else.

Mom gave me a sad look. “Screaming, Perry, really?”

I rolled my eyes and focused on the scenery flying past. “It was nothing. I don’t even remember what it was about.”

That was a total lie. I remembered it more clearly with each hour. Sharp, pointless details like the snags that ran along the lace trim of my nightgown.

I could feel my mom and Ada still staring at me. They were worried. It was the last thing I needed.

You see, I hadn’t made life easy for my family. Despite a relatively normal upbringing, I was always a “problem child” in some way. When I was young, in the single digits, I had a lot of imaginary friends (and, scarily enough, enemies). Well, I actually thought they were real (my imaginary horse, Jeopardy, was the best), but it turns out I had an extremely overactive imagination and my friends weren’t real after all. My parents were freaked out about this and shuttled me off to numerous psychologist-type people to find some “cure.” To be honest, I don’t remember much about that time. Maybe it’s all been repressed, I don’t know, but whatever was done to me worked. My horse ran away, never to come back, and my parents calmed down.

That was until high school, where I was quite the unhappy camper. I was fat (or at least too overweight for high school normalcy). I had a few friends, but I still felt alone. People made fun of me. Girls were mean, and the boys...well, the bad ones were atrocious and the good ones were somehow worse. I was their pal, their confidante, but never their girlfriend. I got to listen to them wax on about how pretty and how hot certain girls were and then I got stuck with the shit end of the stick.

Things went downhill fast and my mental health took a real hit. Stupidly, I dabbled with drugs. A lot of pot, a lot of booze, some pain pills I’d sneak from my mom, sometimes acid. I tried cocaine too, in an extremely stupid and extremely vain belief that it would make me lose weight. I didn’t lose any weight - I only got fatter. And angrier. I try not to regret a lot of the things I’ve done, but I regret doing drugs. It only made my condition a lot worse, to the point where I felt like I lost all touch with reality.

Going with the territory, I also started cutting myself on my arms for attention, writing terribly tragic poems, and just reveling in all-around darkness. I know it sounds cavalier to admit that, but I accept it as a terrible phase I had to go through. I hated everyone and everything, especially my parents and, most of all, myself.

I still have scars on my arms from the cuts. They are faded—almost gone—but they are there, as are the scars on my heart. My story isn’t that unique from many other people’s but sometimes I wonder if I would still feel so lost and angry if I hadn’t had to go through all of that.

I looked at Ada. She’s only fifteen and she’s got it all. Sure, she’s a grump most of the time, but she’s immensely popular, has the most covetable wardrobe ever and she’s got a mild level of fame going on. I was the one hoping (secretly, inside) that somehow I would be plucked from the masses and made an example of. Look at Perry now. She was a hopeless, chunky mess, and now she’s on top of the world.

But it hasn’t happened for me, and as I lose my faith and optimism as I get older, I don’t think it ever will. But Ada, she’s already there and though I’m in front of her, I’m still in her shadow. My sister is a reminder of how unfair life is. No wonder our relationship is complicated.

I looked at my mom and gave her my most sincere smile.

“I’m fine mom, really. Just tired lately. That’s about it.”

She shook her head and turned back, but I could see a weight lifted from her forehead. “It’s all that coffee you drink, Perry. Not good for you!”

Actually, I wanted to tell her researchers recently found a wealth of evidence that suggests coffee actually prevents a multitude of diseases. But I suppressed my need to inform and just sat back in my air-conditioned nightmare as we piloted toward the coast.

***

Arriving at my uncle’s place is such a hectic occasion. Being a bachelor, Al never really had a notion of preparing the house or acting like a host, so our gatherings were usually a bit unconventional.

My cousins Tony and Matt were sitting lazily on the couch playing video games while Al fired up the BBQ in the backyard. The kitchen was an absolute mess.

My uncle and his sons didn’t live on any ordinary property. No, they inhabited a magnificent plot of oceanside land south of the tourist hamlet of Cannon Beach. It used to be a dairy farm that belonged to Al’s ex-wife, but she left it (and her kids) to him when she ran off with a pilot to Brazil or someplace. The cows are long since gone, and the land presently consisted of barren fields of tall, rut

hless grass and a huge barn that used to enthrall me when I was kid (I love cows) but now just gave me the creeps.

Not as much, though, as the structure on the opposite side of the hundred-acre property—the lighthouse. The back yard was essentially a long sweeping lawn with pockets of ruddy sand dunes and rocks running into the wild ocean. To the left of the beach and up a small cliff (and out of view of the house) sat the dilapidated lighthouse. I wasn’t exactly sure whose responsibility it was before, but it was now part of Uncle Albert’s sprawling mass. From what I did know, it had been out of commission for maybe fifty years and Al had no interest in taking care of it. It sat there forgotten and lightless, a darkhouse overlooking the sea.

I had actually never been inside the lighthouse. My curiosity and morbid fascination had been no match for the strict warnings of my family, but I know Tony and Matt had broken in a few times with their friends.

I had a sudden inclination to see if Matt and Tony would be up for exploring it later. I felt drawn to it more than usual, as if visiting the lighthouse would put my present “situation” into perspective.

That would have to wait. As usual, my mother, Ada and I went to work helping Uncle Al and the boys put together a somewhat functional BBQ, cleaning up the kitchen and setting the outdoor table for the feast.

It really was unusually gorgeous out. I was actually a bit disappointed, if you can believe it. The sunshine was remarkable, but the lack of wind meant the wild ocean, which I usually felt cleansed my mind of all its crap, was tame and subdued, the waves lapping gently at the distant shore. And my favorite phenomenon—the mist—was nowhere to be found.

Their place was situated right before the Pacific Coast Highway climbed up to loftier heights and it was at this junction that the Pacific Ocean hurled giant platforms of mist and fog toward the coast, trapping them on either side of the property. To watch these fog beasts roll in was one of the things I liked best about visiting my cousins. There was something so other-worldly about these masses of fog and the way they slowly inched towards the land, coming forward with each rhythmic crash of the rolling waves to hover just above the surface like a continent-wide mothership.

Hot Shot

Hot Shot Maverick

Maverick Love, in Spanish

Love, in Spanish The Lie

The Lie Wild Card

Wild Card Dirty Angels

Dirty Angels Black Hearts

Black Hearts Shooting Scars

Shooting Scars Love, in English

Love, in English Winter Wishes

Winter Wishes Sins & Needles

Sins & Needles On Every Street

On Every Street The Devils Metal

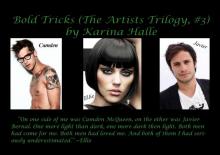

The Devils Metal Bold Tricks

Bold Tricks Old Blood

Old Blood The Play

The Play Into the Hollow

Into the Hollow Dust to Dust

Dust to Dust Before I Ever Met You

Before I Ever Met You Darkhouse

Darkhouse The Debt

The Debt The Devils Reprise

The Devils Reprise Ashes to Ashes

Ashes to Ashes Come Alive

Come Alive The Wild Heir_A Royal Standalone Romance

The Wild Heir_A Royal Standalone Romance On Demon Wings

On Demon Wings The Royal Rogue

The Royal Rogue The Devil's Reprise: A Rockstar Romance (The Devils Duet Book 2)

The Devil's Reprise: A Rockstar Romance (The Devils Duet Book 2) Red Fox

Red Fox The Royals Next Door

The Royals Next Door After All: A Hate to Love Standalone Romance

After All: A Hate to Love Standalone Romance Lying Season

Lying Season Ghosted: Experiment in Terror #9.5

Ghosted: Experiment in Terror #9.5 River of Shadows

River of Shadows Rocked Up

Rocked Up The Devil's Metal: A Rockstar Romance (The Devils Duet Book 1)

The Devil's Metal: A Rockstar Romance (The Devils Duet Book 1) Dead Sky Morning

Dead Sky Morning Old Blood - A Novella (Experiment in Terror #5.5)

Old Blood - A Novella (Experiment in Terror #5.5) Racing the Sun

Racing the Sun Dirty Promises

Dirty Promises All the Love in the World: A Holiday Anthology

All the Love in the World: A Holiday Anthology Song for the Dead: An Ada Palomino Novel

Song for the Dead: An Ada Palomino Novel And With Madness Comes the Light

And With Madness Comes the Light After All

After All Smut

Smut Dirty Deeds

Dirty Deeds Bright Midnight: A Second-Chance Romance

Bright Midnight: A Second-Chance Romance The Dex-Files

The Dex-Files The Benson

The Benson The Offer

The Offer One Hot Italian Summer

One Hot Italian Summer And With Madness Comes the Light (Experiment in Terror #6.5)

And With Madness Comes the Light (Experiment in Terror #6.5) Winter Wishes (The Play #1.5)

Winter Wishes (The Play #1.5) Smut: A Standalone Romantic Comedy

Smut: A Standalone Romantic Comedy Ashes to Ashes (Experiment in Terror #8)

Ashes to Ashes (Experiment in Terror #8) Rocked Up: A Novel

Rocked Up: A Novel Into the Hollow (Experiment in Terror #6)

Into the Hollow (Experiment in Terror #6) Maverick (North Ridge #2)

Maverick (North Ridge #2) Shooting Scars: The Artists Trilogy 2

Shooting Scars: The Artists Trilogy 2 Nothing Personal: A Standalone Romantic Comedy

Nothing Personal: A Standalone Romantic Comedy On Demon Wings (Experiment in Terror #5)

On Demon Wings (Experiment in Terror #5) Black Hearts (Sins Duet #1)

Black Hearts (Sins Duet #1) Darkhouse (Experiment in Terror #1)

Darkhouse (Experiment in Terror #1) Dirty Souls (Sins Duet Book 2)

Dirty Souls (Sins Duet Book 2) The Benson (Experiment in Terror #2.5)

The Benson (Experiment in Terror #2.5) Hot Shot (North Ridge Book 3)

Hot Shot (North Ridge Book 3) Bold Tricks tat-3

Bold Tricks tat-3 Where Sea Meets Sky: A Novel

Where Sea Meets Sky: A Novel